git add . sets you up for failure, and it’s most prevalent in the community that it’s worst suited for: git beginners. Fixing a commit with unwanted changes in it is significantly harder than being intentional about what you commit to begin with. This article will go over how to make intentional commits, and then discuss the most common examples where I see git add . trip up developers.

git add . adds everything from your current folder.

- version changes to lockfiles

- editor config files

- debugging statements

- random unwanted whitespace changes

- changes you actually want

- changes you thought you wanted, but don’t

Instead, I want you to intentionally add changes to your commit using git add -p, and I want you to add new files using git add filename or git add foldername.

Intentional Git Commits

1 - git status

> git status

On branch main

Your branch is up to date with 'origin/main'.

Changes to be committed:

(use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

modified: _config.yml

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: Gemfile.lock

modified: _layouts/stretch.html

modified: _posts/2023-06-25-fibonacci-shawl-pattern.md

modified: _sass/layouts/_stretch.scss

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

_posts/2023-07-09-stop-git-add-dot.md

_posts/vim-commands.md

_sass/base/

assets/img/profile_pic.JPG

2 - git add <filename|foldername>

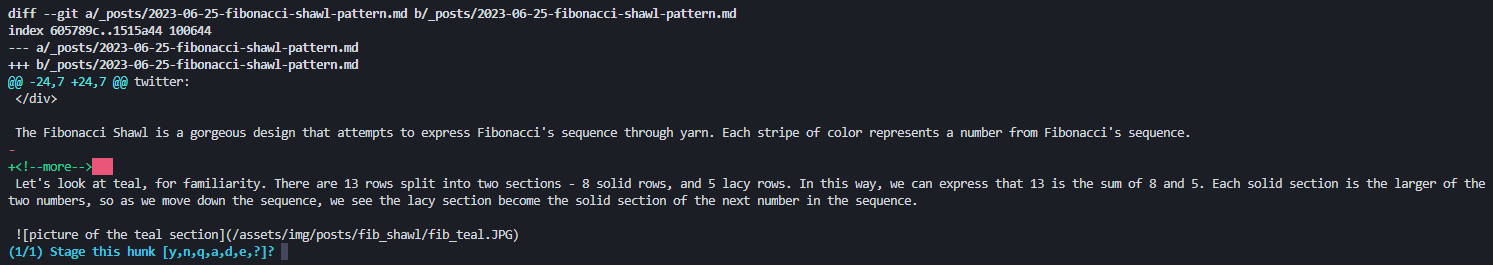

3 - git commit -p

> git commit -p

diff --git a/Gemfile.lock b/Gemfile.lock

index 8a0eca6..e94d073 100644

--- a/Gemfile.lock

+++ b/Gemfile.lock

@@ -43,6 +43,7 @@ GEM

listen (~> 3.0)

jekyll-youtube (1.0.0)

jekyll

+ json (2.6.3)

kramdown (2.4.0)

rexml

kramdown-parser-gfm (1.1.0)

(1/3) Stage this hunk [y,n,q,a,d,j,J,g,/,e,?]

>

There are a lot of different options for the hunk you’re working for. Use ? to see a printed list of them and select the best one for the situation. Some of my favorites are y for “yes, I want this hunk”, n for “no, I don’t want this hunk”, d for “don’t ask me again about this file”, and e for “edit”.

(1/3) Stage this hunk [y,n,q,a,d,j,J,g,/,e,?]? ?

y - stage this hunk

n - do not stage this hunk

q - quit; do not stage this hunk or any of the remaining ones

a - stage this hunk and all later hunks in the file

d - do not stage this hunk or any of the later hunks in the file

g - select a hunk to go to

/ - search for a hunk matching the given regex

j - leave this hunk undecided, see next undecided hunk

J - leave this hunk undecided, see next hunk

e - manually edit the current hunk

? - print help

Generated Files

We’re often using scaffolds or generate commands to create new files or the application. I recommend creating a commit immediately after running that command with the command as the commit message. Then all your future commits will be covered by patch adding, and you’ll have a history of what the command generated vs what’s hand-crafted.

When git add . Doesn’t Cut It

Unwanted Untracked Files

Sometimes I’ll have files locally that I don’t want to commit. node_modules, editor configs, and logfiles immediately come to mind. You can permanently exclude these by adding them to your .gitignore, but accidentally duplicated and renamed files, blog posts that aren’t ready yet, or scaffolded files I don’t need are all examples of files that can’t go into gitignore, but I don’t want them yet.

git add . throws all of these into the commit without so much as a warning, but you’ll never have this issue if you’re intentionally adding files.

Lockfile Updates

I see this one all the time and it’s especially nasty. During the course of regular development and installing dependences, the version manager’s lockfile gets updated with some patch changes. Your pull request isn’t about version changes. git add . will add those changes anyway, in the same commit as the changes you actually want. This one is especially nasty because everyone tends to get these patch updates at the same time, and then there’s merge conflicts galore, even if you reverse the changes in a second commit. Especially if you reverse the changes in a second commit.

d for “Don’t add the lockfile”.

Unintentional Whitespace

It’s really hard to see extra whitespace at the end of a line in your editor. git add -p highlights that whitespace in red, you can remove it from the commit without exiting by using the edit option.

e for “Edit out extra whitespace!”

Debugging Statements

In the course of problem-solving, we dump debugging statements, commented out debugging statements, and tiny code changes to make debugging easier throughout the application. Skip all those, or edit them out of the final commit, and have beautiful, clean, readable commits that don’t cause merge conflicts or break the build.

n for “Not this console.log…”

e for “Edit that out!”

Local Environment Changes

I use WSL with Docker and Rails’s default filechecker doesn’t like that, so I have to override it and use a less performant version in all the apps I work with. This is an unusual development setup, and I don’t expect every app I work with to adopt my filechecker. I just skip this change whenever I make a commit with git add -p. Another common scenario is replacing an API key in your local environment and leaving the original in higher environments. Sometimes you need to tweak things locally, but it might not be appropriate to update the repo with that tweak.

n for “Never add this.”

Separate commits with discrete changes

Ideally commits will describe one discrete change to the codebase, but realistically we make lots of little changes at the same time. In order to create discrete changes with git add ., you have to remove any extraneous changes, or be disciplined about committing after every change and only working on one change at a time. git add -p lets you be more flexible and extract out one discrete change at the end. These discrete commits are easier to cherry-pick into other branches, and make your PR easier to review for other developers.

n for “Not yet!”